Theatres of Medicine, Inside and Outside the Hospital

Covid-19: public buildings are urgently repurposed to hospital facilities, hotels and exhibition spaces turned into critical care facilities. What do medical spaces, educational and clinical, tell us about how we interact with, and remake, specific environments? How is knowledge about the body mutually constituted and enacted? In my work on the Performing Medicine Project I analyse medical scenographies, namely, the material arrangement and experience of medical spaces, as performative environments where boundaries between bodies and objects are redrawn, from a post-human perspective. This perspective applies, for instance, in surgery: when robotic arms become lead characters in the operating theatre, they delineate the body of a surgeon, who works remotely in a console.

Scene 1. Medical Scenography

Scenography is a term which evokes the image of a carefully crafted and decorated stage set in a traditional theatre. Viewing frames and different points of view guide our attention through the confines of physical architecture, and the dynamics of shadow and light. Movement and stillness are constituted through our interactions with an environment and the ways in which we reposition ourselves in relation to other performing bodies and objects. More recent theories about performative environments visualise scenography as a kind of body in its own right. This body has physical dimensions, and its own spatial logic. And it teaches us about the ideas, practices and ethics that constitute its suggestive and political power. An anatomy theatre, for instance, elevates the observer to a position that looks at the open body from above, almost with a bird’s-eye perspective, by enacting a logic of turning inside-out. This anatomical device uncovers the shared practices through which we are separated and connected. I imagine scenography as a shared body or the spatial articulation of our experience, brought into existence by our interactions and through material arrangements, which in turn performs us, not at least by inspiring us to act. Looking beyond the picture stage in this way, scenography extends to institutional spaces, including the public and private settings through which we all move. Role changes make the performative character of these extended scenographies particularly tangible.

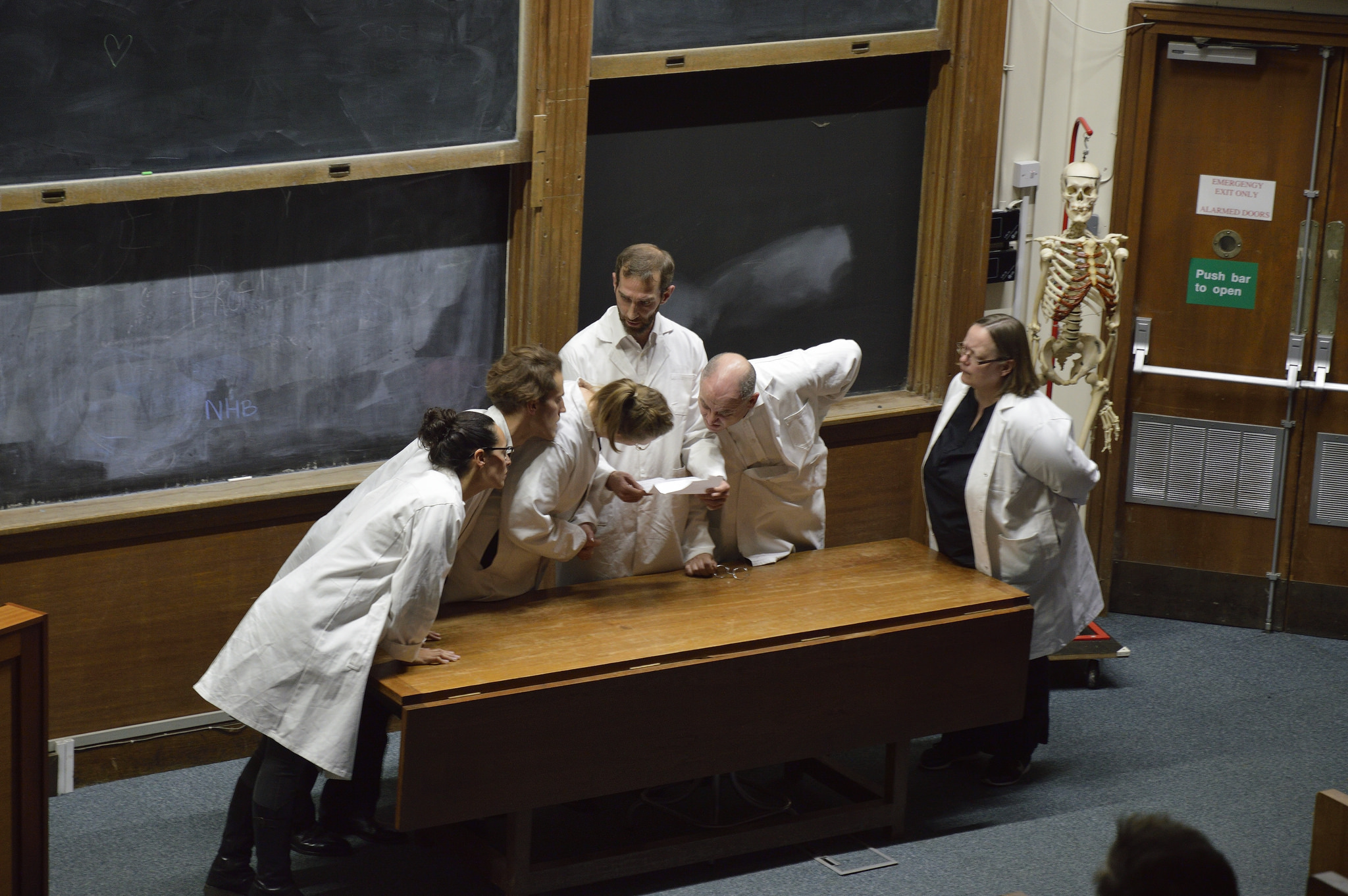

The scenographies of my research extend from an office desk (during the Coronavirus outbreak my work is lodged between virtual and analogue environments in the physical confines of my living space) to the proscenium of live theatre; and from there to the different educational and clinical settings of my professional life. Here I act as a literary scholar, with a background in German Studies, Cultural Anthropology and Digital Humanities. In these capacities, I produce and direct public theatre performances; and, in response to my surroundings, take on the roles of dramaturge and anthropologist. My work on theories of embodiment is significantly informed by engaging with a set of performative practices in real and fictive medical settings. I like to bring a dramatic text to life in the very institutional spaces which constitute its meaning. For instance, I produced a series of performances of Arthur Schnitzler’s hospital drama Professor Bernhardi (1912) in St Bartholomew’s Hospital (see figure 1), London, as well as in the Anatomy Lecture Theatre at Cambridge’s Downing Site (see figure 2). This site-specific production was staged by the east London-based theatre company [Foreign Affairs] in an abridged adaptation by Dr Judith Beniston (Co-Investigator of the Schnitzler Digital Edition Project) and Dr Nicole Robertson.

My work with the Cambridge Human Anatomy Teaching Group, in collaboration with the clinical anatomist Dr Cecilia Brassett (2009), uses theatre as a model to investigate how medical students perform role changes and enact doctor-patient relationships in the dissection room. Performing Medicine is advancing the research of Year 3 medical students, who are investigating the practice of anatomical education temporally and spatially. Their engagement with Critical Medical Humanities is not only changing how research is conducted; it also creates critical awareness of how we can manipulate performative environments through physical architecture, role changes, digital technology, and ethical awareness.

Scene 2. Entangled Embodiment

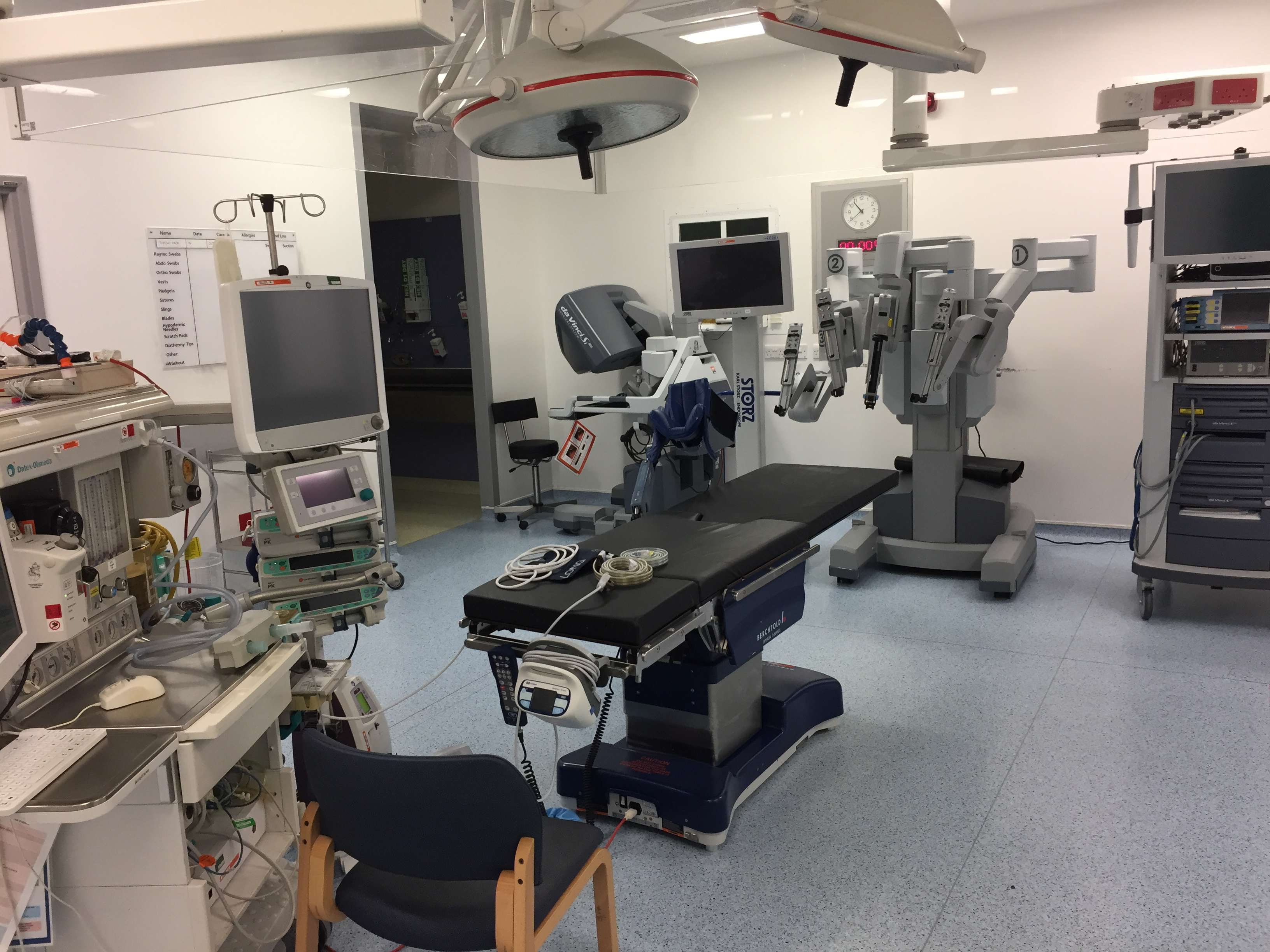

What if the line between subjects and objects is constantly in flux? How does the da Vinci robot redraw bodily borders? In my most recent field work on Performing Medicine I collaborate with the data scientist and Intensive Care consultant, Dr Ari Ercole (2014). This work extends medical scenography to clinical settings. At Addenbrooke’s Neuro Intensive Care Unit, for instance, I am analysing the entanglement between technologies of embodiment and clinical practices, moving from the motions of a ward round to the clinical light of the operating theatre. In both medical settings, educational and clinical, I examine how performative practices are translated to virtual environments. Digital tools such as three-dimensional models and tablet computers increasingly guide how medical students interact with cadavers in human anatomy classes. Equally, virtual reality and robotic surgery have reconfigured the stage set in some operating theatres and side-lined the surgeon, who now operates remotely in a surgical console, with their head immersed in a virtual projection of the patient’s body while the surgeon’s fingertips control four robotic arms at centre stage.

New technologies reconfigure medical spaces and prompt role changes, most significantly through the ways in which bodies are mutually constituted or remediated, e.g. through book knowledge or bits of data which render a body in virtual reality. In a clinical setting, this raises questions about the doctor-patient relationship. What do we lose by not touching a patient? How will machine learning influence how we experience and co-create clinical environments?

My key interest lies in two-way interactions between medicine and the arts. Arguably there is nothing else like the theatricality of medical spaces: while they put us in a unique position to read bodies, these environments read us in return. The way we choose to interact with them reveals our relationship with our surroundings, and with health and illness more generally. In other words, medical spaces act like magnifying glasses. They enlarge the practices through which we co-constitute our realities. In the past few weeks, and against the background of the coronavirus pandemic, extended scenographies, in public and in private, have been drastically reconfigured. Today our living spaces are repurposed to work spaces and can rapidly become territories of quarantine. Returning to the shared body that is scenography, our interactions and practices articulate new ways in which we are embodied through these increasingly hybrid spaces. In a time when acts of repositioning are not only directed through social distancing rules but also mediated through virtual environments, my future work on the reconfiguration of diagnostic medical spaces, in real and fictive settings, focuses on digital tools and new theatrical formats to help us to read these new realities.

Scene 3. Dr Tulp’s Communities of Reading

In my new role as an Isaac Newton Trust Postdoctoral Fellow in the Cambridge Digital Humanities, I read medical spaces through the literary, visual, performative, and digital, arts. Rembrandt’s canonical group portrait The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp (1632) provides the starting point for a book project on Tulp’s ongoing presence in real and fictional institutional spaces from the late nineteenth century to the present day. A recent re-performance of Rembrandt’s painting showed how its scenography heightened the consciousness and awareness of spectators in the gallery and how they experienced their own bodies as part of a community of readers (see figure 4). Above all, it is the practice of reading as well as acts of interpretation and of diagnosis which are at stake in the theatrical space of this image; reading the re-enactments of the Rembrandt-Tulp theatre we can begin to shape a new narrative of the relationship between medical science, literature and the performing and digital arts. My findings suggest that scenographies in anatomy theatres or operating theatres enact a logic of turning inside-out by making visible boundary-making practices relating to the ways in which agents, subjects and objects, are materialized and embodied. I analyse these medical scenographies in real and fictive settings in which Dr Tulp and his group of anatomists re-appear. This includes a clinical laboratory in Christian Petzold’s film Barbara (2012) and the operating theatre in David Wagner’s novel LIFE (2013) and Maylis de Kerangal’s novel Mend the living (2016).

A fresh line of inquiry will invite the public to participate in Dr Tulp’s communities of reading. Drawing on augmented reality (AR) technology and LiDAR scanning, I will develop a ‘Staging Medicine’ AR application and a mixed reality drama in which participants can analyse and repurpose their surroundings by manipulating and experiencing how their bodies materialize across different media and settings, moving from a public anatomy to a hospital ward up to a heart transplant scene. Rembrandt’s Anatomy thus serves as the entry point for an understanding of changing scenographies of healthcare, reconfigured bodies and spaces by asking how we cut up the world around us and reconfiguring the roles we are playing in it. Intersecting practices between new technologies and research-based theatre have prompted me to talk to performance scholar Dr Melissa van Drie (Copenhagen), theatre director Bertrand Russel (theatre company potential difference, London) and dramaturge Imanuel Schipper, who collaborates with the internationally renowned theatre group Rimini Protokoll, with the aim to create an interactive environment inspired by the case of Rembrandt’s Dr Tulp. Links to theatre directors were partly forged and established through conversations with alumni and benefactors of the College.

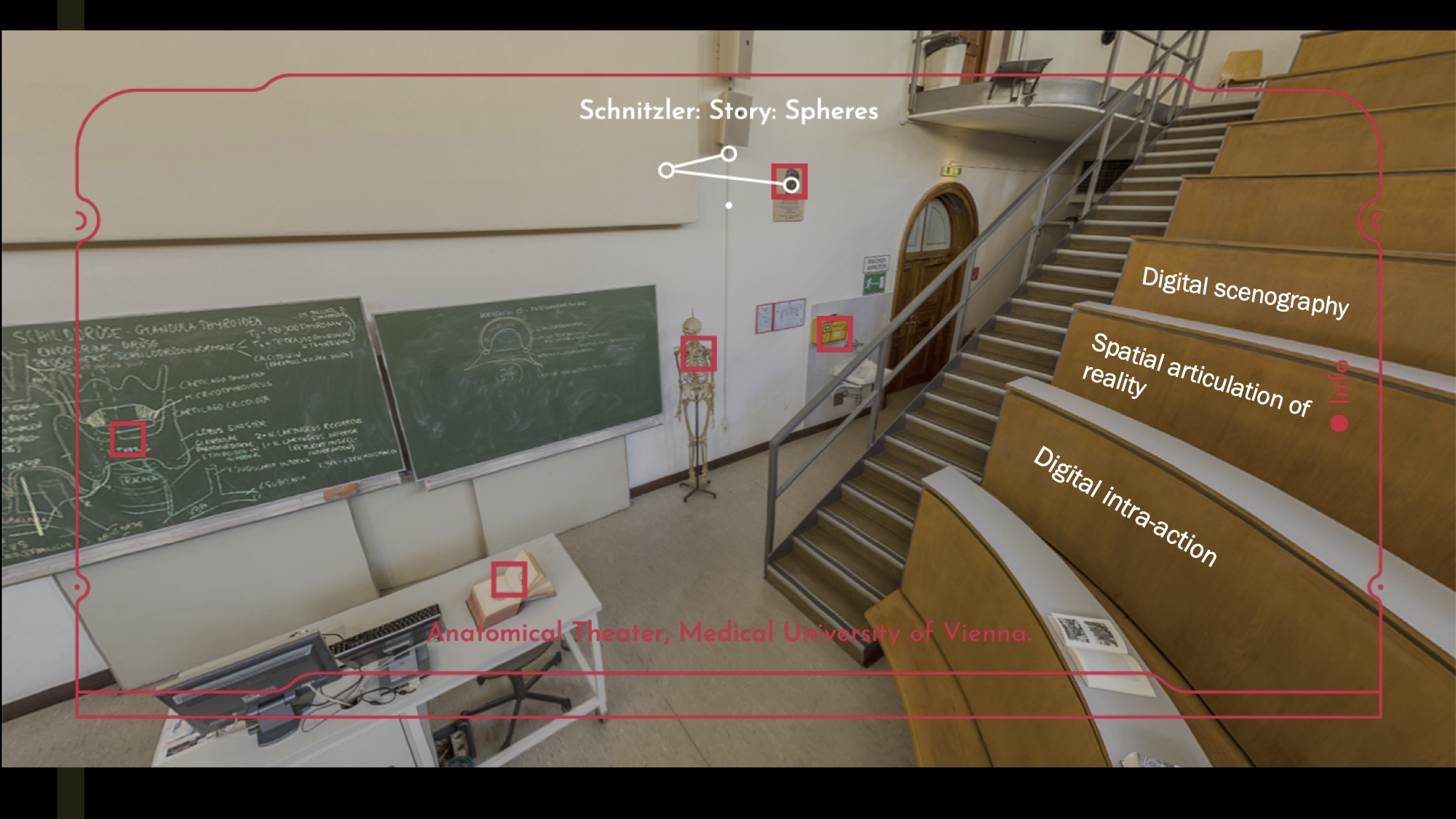

Scene 4. Digital Scenography and Knowledge Design*

My dramaturgical inquiry on virtual and augmented realities builds on previous work in the digital humanities. This work focused on Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), one of the most important doctor-writers in twentieth century Europe, whose dramatic writing is profoundly shaped by medical spaces and his experience as a medical student and Austrian Jewish physician in Vienna around 1900. His ‘archive in exile’, which houses a large part of his literary estate, is held by Cambridge University Library. A major international edition project has for the first time made Schnitzler’s middle and late period drafts freely accessible, saved from destruction by the Nazis in 1938. I am lead editor of a scholarly edition of Schnitzler’s cycle of puppet-plays Marionetten (hosted by the Cambridge University Library: https://www.schnitzler-edition.net/genetisch). My work on his dramatic experiments with the human body and free will has uncovered the surprising extent to which Schnitzler used medical scenography to stage his own writing process and to dissect social and political developments such as the entanglement of anti-Semitism with institutional spaces. My archival work engages with the performative environment of the University Library in creative and unprecedented ways. My site-specific production of Schnitzler’s theatrical parody The Great Wurstel (April 2019) was the first ever public play to be staged in Cambridge University Library in its 600-year history (https://www.cam.ac.uk/SchnitzlerPlay). This seemed particularly fitting, because the drafts and manuscript are held in close proximity to the Library’s Rare Books Reading Room where my experiment with cultural space took place. All participants, especially those who play-acted as members of the audience, transformed the quiet and studious space of the Reading Room into the site of physical spectacle that is the Prater, Vienna’s famous amusement park. The sell-out production was enthusiastically supported by an ensemble of student actors, and academic actors from my team, all working in close collaboration with the University Library. Other major contributions came from the British artist Richard Wentworth, and the translator and co-director Ada Günther.

Trailer for The Great Wurstel

A year later, at a time when most institutional spaces have closed their doors for an indefinite period, many of us are reconfiguring our realities and adapting to new ways of working. In these circumstances, Schnitzler’s human puppet play only becomes more topical. It explores what it means to be human in a world controlled by machines. I am also writing at a time when many events have been cancelled, and when we are being asked to rethink our research agendas, and consider how they might translate into digital formats. My ideas on digital scenographies aim to establish a proscenium here and now, in lieu of an event in the University Library. This will involve launching an interactive digital environment: the Schnitzler: Story: Spheres.

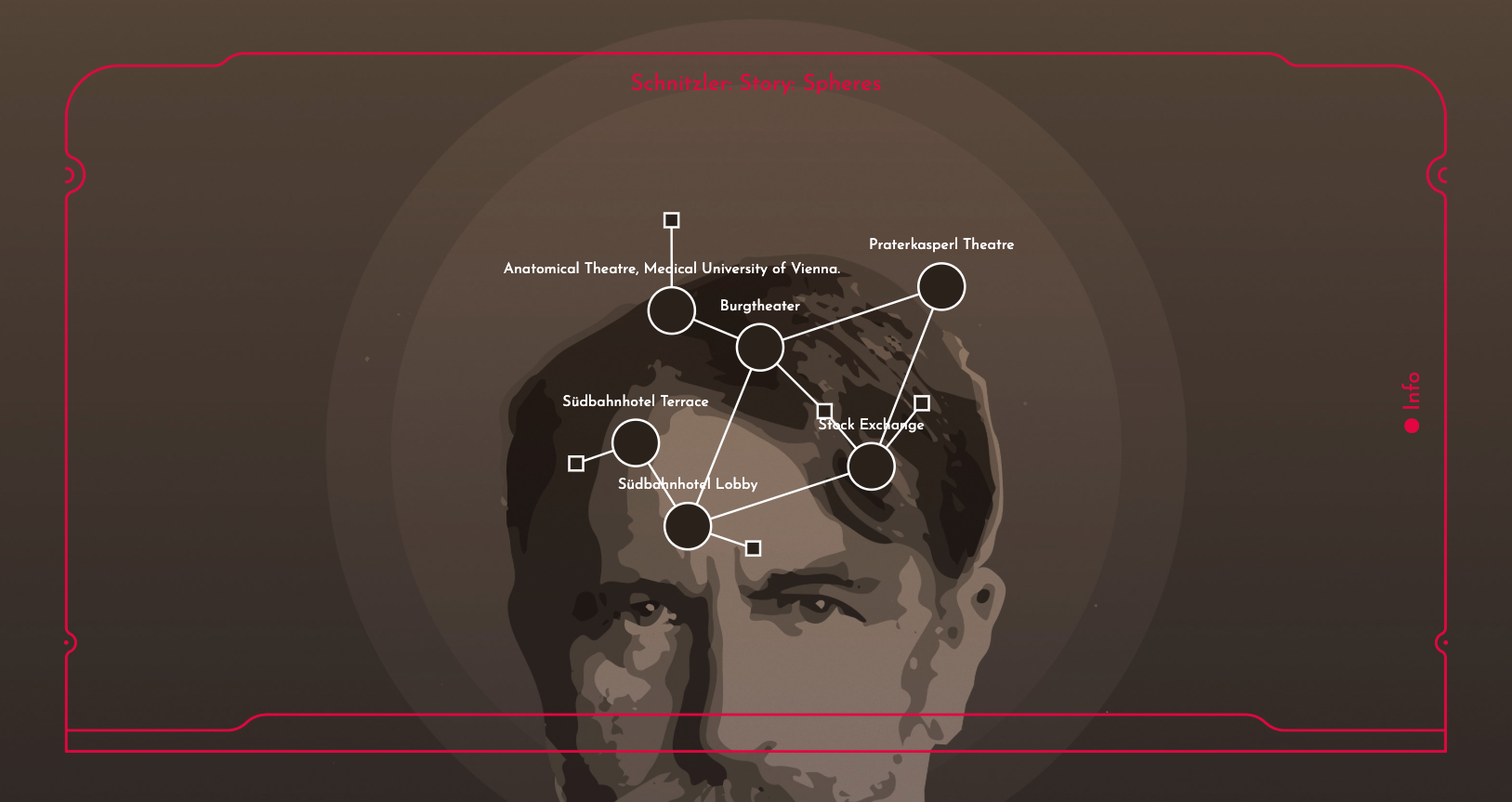

The Schnitzler Spheres are a network of 360-degree spherical photos, which render six interactive environments, showing places at which the storylines of Schnitzler’s life and imagination intersected. The concept for the prototype has been developed by digital artist Frederick Baker in collaboration with the Games Studio Lost in the Garden. I co-developed this digital tool together with Baker, alongside Andrew Webber (Principal-Investigator for the Schnitzler Digital Edition Project), digital experts, and many artists and practitioners based at six interlinking locations in and around Vienna. We developed this prototype with the vision that additional funding would allow us to connect the Schnitzler spheres to the imaginaries and geopolitical locations of other important figures, who are displaced and excluded from the canon. As a creative form of public engagement and a new approach to curating and modelling knowledge the spherical logic inverts the location of the spectator by projecting us, in the role of experimental topographers, into the centre of the spectacle: http://schnitzler-spheres.lib.cam.ac.uk/.

As we navigate each sphere the dramatic viewing apparatus provokes a continuous change of perspective. We start by watching a Punch-and-Judy show in the Praterkasperl sphere, at which point – turning through 180 degrees – the audience takes centre-stage. In the Anatomical Theatre sphere our viewpoint is elevated to a birds-eye perspective, which draws our attention to Emil Zuckerkandl’s Anatomical Atlas in the centre of the room, this being a familiar view and location for Schnitzler during his time as a medical student.

Schnitzler’s medical drama, Professor Bernhardi, explores the disposition of bodies in these medical places as they are subjected to institutional power. The case of Bernhardi, which is enacted in Schnitzler’s fictive hospital, as well as heard in court and debated in parliament, takes us through some of the key institutional spaces of the ‘wide domain’ of the Habsburg monarchy. The grand hotel is another such space, where the personal and socio-political dynamics of the monarchy are played out. Moving out of Vienna, to the recreational space of the Semmering, we can take a seat in the lobby of the Südbahnhotel sphere and observe the behaviour of guests as they enter this social stage. Schnitzler used to spend hours doing the very same. Above all, the viewing frame of the spheres creates a play-within-a-play, a structure that explores the interplay between the social arena and the theatre.

This projection of life into theatre takes us full circle to Schnitzler’s comedy The Great Wurstel and a new performance space or booth, a marionette theatre, surrounded by visitors to the so-called Wurstelprater. If you work out how the Praterkasperl Theatre is cut up and connected, and so known, by clicking on hotspots, marked by a square, you can find yet another viewing frame where the film version of the performance of Schnitzler’s burlesque fairground comedy is presented in the Punch-and-Judy box. This one-act play, in turn, reflects upon the entanglement of the human in the broader apparatus of theatre, theatre understood as a paradigmatic social institution, and the apparatus of society – that is, as theatrum mundi.

* The last scene ‘Digital Scenography and Knowledge Design’ ‘rehearses’ a passage which was first published in an interactive essay which I wrote collaboratively with Frederick Baker and Andrew Webber as part of the Schnitzler Spheres (for the full version of ‘Schnitzler: Story: Spheres: An interactive essay’ see info box in the Spheres).

By Dr Annja Neumann (2014)