Library and Archives

Mark vs. Tristram

It is 70 years since C S Lewis, the renowned author of over thirty books on literature and theology as well as the world-famous Narnia chronicles, came to Magdalene College as the new and first Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature.

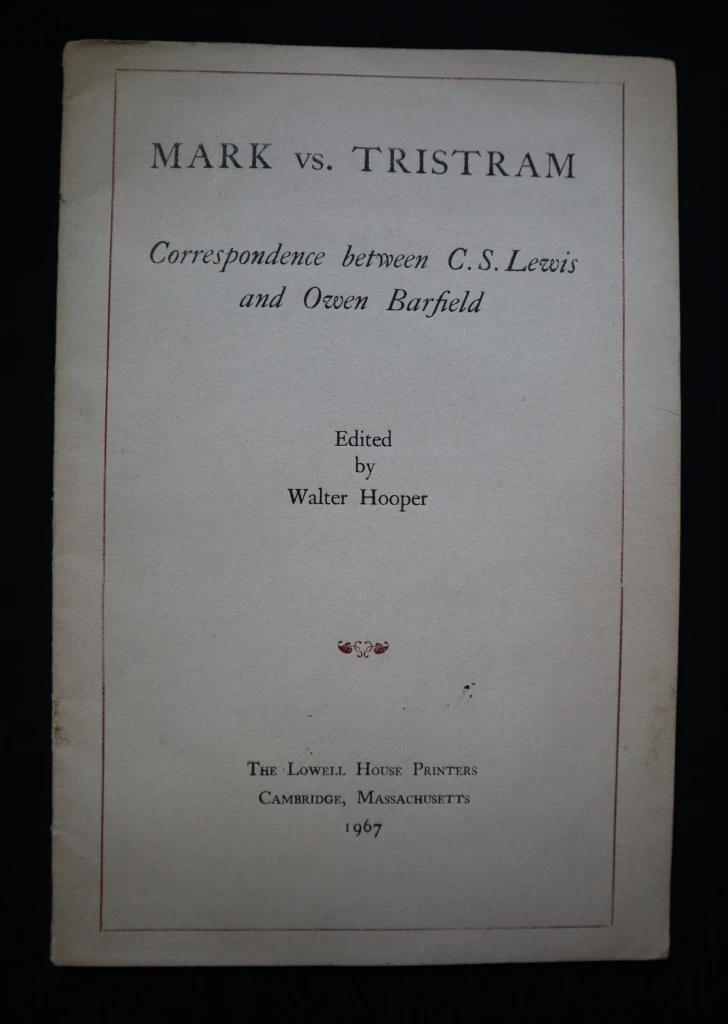

Here, one of his distinguished successors in this post and a life fellow of Magdalene, Professor Helen Cooper, writes about an intriguing and entertaining piece by Lewis, preserved in the Old Library: Mark vs. Tristram: Correspondence between C.S. Lewis and Owen Barfield, edited by Walter Hooper (The Lowell House Printers, Cambridge, Mass., 1967), no. 60 of 126 copies.

One of the less conspicuous items in the Old Library is a booklet of a few pages – little more than a pamphlet – purporting to contain the correspondence between the solicitors for King Mark of Cornwall and Sir Tristram. The case concerns the king’s institution of divorce proceedings on the grounds of the knight’s ‘criminal conversation’ with his wife, together with a threat of action in the King’s Bench Division against Tristram for enticement unless compensation is paid for the ‘grievous injury’ Mark has suffered. This all relates, of course, to the legend of Tristan and Isolde, one of the great love stories of all time, much retold in poetry, fiction and opera. King Mark had sent his nephew Tristan to bring the Irish princess Isolde back to Cornwall to marry him, but on the voyage the young couple unknowingly drank a love potion intended for Isolde’s wedding night, and their love was fated from that moment on.

The letters are dated to the year 503, a reasonable supposition based on the legendary histories of King Arthur, with which the story of Tristan and Isolde had become associated in the twelfth century. In cold fact, they were written some time after Eugene Vinaver’s publication of the newly-discovered manuscript of Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur in 1947, the work that in due course became the foundation of all later anglophone Arthurianism, including Monty Python and the Holy Grail and the fast food shop in Tintagel named Excaliburgers. Until the manuscript was discovered, the Morte had been known only in the somewhat different form of Caxton’s 1485 print. It was that version that had become standard adventure reading for Edwardian children (boys in particular), together with its introduction applauding its teaching of manly virtue; its readers had included Lewis and no doubt Owen Barfield too. The friendship between the two men was established in 1919; later they were key members of the Inklings, the literary group that met in the Eagle and Child (otherwise known as the Bird and Baby) in St Giles in Oxford. Barfield was a solicitor by profession, but by vocation he was a critic and philosopher, and his ideas deeply influenced both Lewis and Tolkien, though not always through agreement.

Lewis wrote a review-essay of Vinaver’s edition when it first came out, and a further article later. In the course of these, he mounted a defence of Malory against the new facts of his life that had emerged through details given in the manuscript: facts that included charges of cattle-rustling, rape, and attempted murder. An exceptionally strong military escort was sent to arrest him, from which he escaped; he was then incarcerated in the less than salubrious prison of Newgate (he describes himself in the manuscript of the Morte as a ‘knight prisoner’). On the surface, all these set Malory in stark opposition to the ideals of chivalry, faithfulness and service to ladies to which the work itself made constant reference, and which Caxton and all those Edwardian schoolboys had taken on trust. Lewis argued that these charges were hostile legal interpretations of actions that could be thought to be far closer to the heart of knightliness than they appeared; but the gap between the two gave space for Barfield’s gleeful intervention. The letters remained unknown until they were published after Lewis’s death by his literary executor Walter Hooper.

English readers had never been as accepting of the adulteries of the Arthurian world as French readers (Lancelot’s affair with Guinevere never reached anglophone readers until the fifteenth century, and there is only one English version of the story of Tristan before Malory), and the opportunity to reframe the story in an alien modern context, as with Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in the Court of King Arthur, offered an open goal. Barfield wrote King Mark’s side of the correspondence on the official notepaper of his firm, Barfield & Barfield. Lewis’s replies were purportedly written by the firm of Blaise & Merlin – Blaise having been the mentor of Merlin just as Merlin was the early mentor of King Arthur. They mount a fierce defence of their client Tristram (Malory’s chosen spelling), less in terms of theoretical argument than by a reminder that trial by battle remained a legal possibility, and Tristram had once killed twenty-five knights who had opposed him. Barfield & Barfield’s tone immediately becomes more conciliatory.

The series concludes with a letter from Maistre Bleyse himself, written in Malorian Middle English, claiming that Tristram was so furious about the correspondence that he had transformed him (Blaise) into an ass; and even after he had been turned back into human form at the ‘great entreatie of many good knights and jentlemen’, he had been left with the ‘unnatural eares and hoofs of that beest’. The closing line contains a veiled threat of the same fate awaiting Barfield & Barfield – at which point the correspondence unaccountably ceases.

Magdalene College has made every reasonable effort to locate, contact and acknowledge image copyright owners and wishes to be informed by any copyright owners who are not properly identified and acknowledged so that we may make any necessary corrections.