Library and Archives

Little Gidding and the Gospel Harmonies

Little Gidding was an Anglican religious community established by Nicholas Ferrar (1592-1637) in Huntingdonshire in 1625.

Made up of Ferrar’s extended family and servants, the community gained attention in the 1630s for their production of biblical harmonies and concordances, produced (at least initially) for the devotional use of the household. The creation of these concordances involved the cutting up of verses from printed copies of the Gospels, rearranging them and pasting them back together. This allowed the gospels to be read aloud as a single chronological narrative and formed an important part of the domestic community’s daily worship. The text was combined with intricately cut images, taken from prints collected by Nicholas Ferrar, many of which he brought back from his earlier travels on the Continent. The process of cutting and pasting (under the direction of Nicholas Ferrar) was seen as a pious activity for women, undertaken by Ferrar’s nieces. The family also produced harmonies as gifts for absent family and friends as well as for commissions from wealthy patrons, including King Charles I[i].

The Old Library holds a collection of surviving prints and an incomplete gospel harmony from the Ferrar’s production room at Little Gidding. The majority of prints are sixteenth-century religious engravings, largely published in Antwerp. A number are in duplicate and some in triplicate; many have been carefully excised. The collection also contains the numerous excised pieces that failed to make it into the completed harmonies.

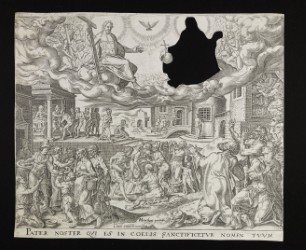

One excised print is Pater Noster qui es in coelis, the first of a series depicting scenes from the Lord’s Prayer, published by Carel Collaert (1598–1654) in Antwerp in the late sixteenth century. The figure of God has been carefully cut out from the sky. Whilst excisions by the Ferrars were largely used to accompany text for their gospel harmonies, excisions were also made for other reasons. For example, God was commonly excised by the Ferrars because using the image of God for worship was prohibited by some Protestant interpretations of the Second Commandment, but the prints Nicolas Ferrar had collected were predominantly Catholic. The engraver of this print was Johannes Wierix (1539-1620), whose work played an important propagandist role in the Counter Reformation in the southern Netherlands. The Ferrar’s excision in the print led it to be exhibited in Tate Britain’s ‘Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm’ (October 2013-January 2014)[ii].

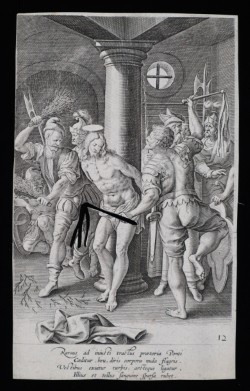

Another print featuring an excision by the Ferrar family is an engraving of the Flagellation, where one of the whips has been excised. Strikingly, the whip has been cut out in one piece, presumably with a scalpel rather than scissors, keeping the rest of the print intact. The excised whip must have been destined for one of the gospel harmonies. The print is part of the Thesaurus Veteris et Novi Testamenti series, a collection of groups of prints portraying the Passion of Christ by different designers and engravers, published together in a single volume by Gerard de Jode in Antwerp in 1585. Another interesting feature of this print is a numerical annotation on the verso: “143”. Many of the prints in the collection have been annotated by Nicholas’s brother, John Ferrar (1588-1657), and either refer to the print’s corresponding chapter in the harmonised gospels or to the print series number.

Not all the prints in the collection depict Biblical scenes. One example is Lapis polaris, magnes (the invention of the compass), part of a collection of nineteen prints from a series titled Nova Reperta, illustrating new inventions and discoveries in the ‘modern’ world, designed by Joannes Stradanus (1523-1605). Here, the invention of the compass is celebrated, highlighting the break from the constraints imposed by the previously unchallenged authority of classical writers[iii]. The inventor, Flavio Amalfitano, is seated at his desk using a compass, surrounded by tools, books and instruments, including an hourglass, an astrolabe globe and model ship hanging from the ceiling. The engraving is attributed to Jan Collaert I (c.1525/30-1580) and was published by Philips Galle (1537-1612) in c.1580-1605. The Ferrar print collection also holds three other prints from the series, illustrating the inventions of distillation, oil painting and copper engraving.

We are pleased to announce that the cataloguing of Ferrar Prints has recently been completed and they are available to search online.

By Isobel Renn

Pepys Library Assistant and Invigilator

All images used in this blog are the copyright of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College Cambridge. To reproduce these images in any format, including online, permission from the College must be sought.

References

[i] Royal Collection Trust, The Little Gidding Concordance, (n.d.) <https://www.rct.uk/collection/stories/the-little-gidding-concordance> (accessed 8 July 2024).

[ii] Barber, T. and Boldrick, S. Art Under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm, (London: Tate Publishing, 2013), pp. 82-3.

[iii] Royal Museums Greenwich, Nova Reperta: Invention of the Compass, (n.d.) <https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-101930> (accessed 9 July 2024).