Library and Archives

Great Fire of London

Welcome to our Virtual Exhibition page, offering online visitors the chance to view items in our special collections and to learn more about them.

We will be curating our exhibitions around themes of particular interest in our collections, starting with 'The Great Fire of London', displaying items from the Pepys Library.

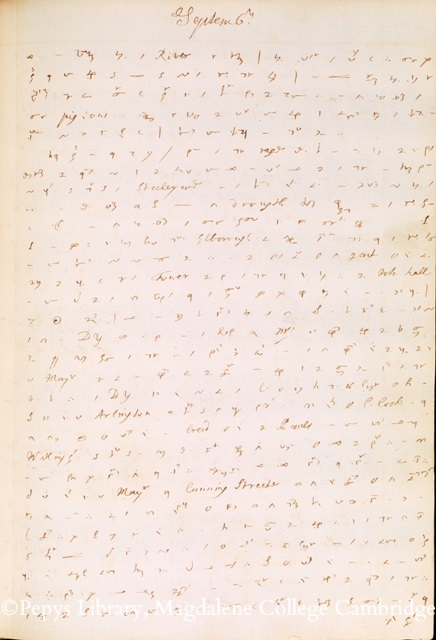

Item 1: Manuscript: An extract of Samuel Pepys’s diary describing the Great Fire

Samuel Pepys’s description of the Great Fire of London is considered the most vivid contemporary account of the event.

Samuel Pepys wrote his diary in shorthand, namely ‘Shelton’s Shorthand’ – a scheme devised by Thomas Shelton, a 17th-century stenographer. Pepys wrote out names and places in full, however, and the occasional word which must have been tricky to convert into shorthand (see ‘pigions’ on the fourth line). An extract from this page reads:

Poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats of clambering from one pair of stair by the water-side to the another. And among other things, the poor pigions I perceive were loath to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies till they were some of them burned, their wings, and fell down.

Item 2: Print: A Map of London showing London after the Great Fire, by Wenceslaus Hollar

This map, ‘An exact svrveigh of the streets lanes and churches contained within the ruines of the city of London’ shows the area affected by the Great Fire in 1666 and its surroundings.

The city was rebuilt with a similar road layout to before the fire to avoid major disputes and negotiations concerning land ownership, and to approach to rebuild with pragmatism. The relevant authorities needed to take into account post-fire labour shortages and a desire to resume everyday life as quickly as possible, so the more ambitious rebuilding schemes in the baroque style never came into fruition.

The largest building to be burnt in the fire, slightly to the left of the middle of the fire-affected area and shaded in grey on the map, is the ‘footprint’ of the medieval St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Item 3: Print: An Engin to quinch great Fires, attributed to William Faithorne

This etching depicts a very early example of a fire engine designed by the London Blackfriars pump maker, John Keeling, during the late 1670s.

The Great Fire of London highlighted the need for better methods of fire prevention and control, and encouraged engineers and innovators to experiment with new firefighting technologies. Seventeenth-century fire fighting was extremely dangerous and those put to the task were often exposed to great risk. Keeling’s engine allowed firefighters to pump water from a central barrel and to wheel that barrel to wherever it was needed.

The engine reflects an important move toward modern firefighting techniques, yet its heavy weight meant that the barrel was slow and difficult to transport, and given the force that would have been required in order to drive the piston, the engine would have had only a limited impact in helping to extinguish a large blaze.

In 2016, the Museum of London restored a similar fire engine in their collections, designed by John Keeling in 1678.

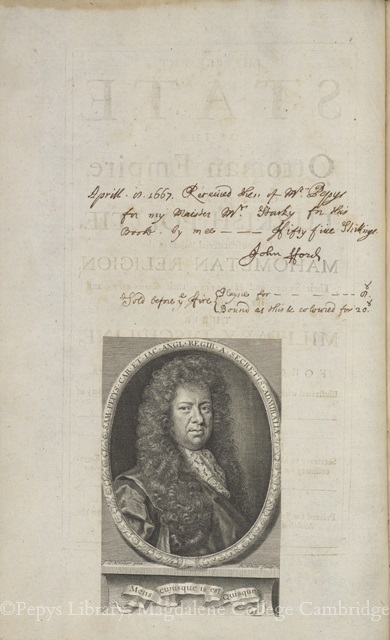

Item 4: Book: The present state of the Ottoman Empire, by Paul Rycaut

Although this book’s title, The present state of the Ottoman Empire, may not have much to do with the Great Fire of London, the history of the production of the book tells us much about the fate of booksellers during this tumultuous time.

Pepys did not tend to write in his books, but he makes an exception in this case, detailing how much the book was on sale for prior to the fire (8 shillings) and its inflated price in the fire’s aftermath (20 shillings).

One of Pepys’s regular booksellers, Joshua Kirton, lost his shop and most of his stock. Most of the booksellers, including Kirton, had businesses around St. Paul’s churchyard. Stationer’s hall, which was used as storage by the booksellers, also burnt in the fire. It is thought that the bookselling was possibly the trade worst affected by the fateful events of 1666. Pepys notes in his diary on 11 November 1668, ‘I hear Kirton my bookseller, poor man, is dead; I believe of grief for his losses by the fire’.

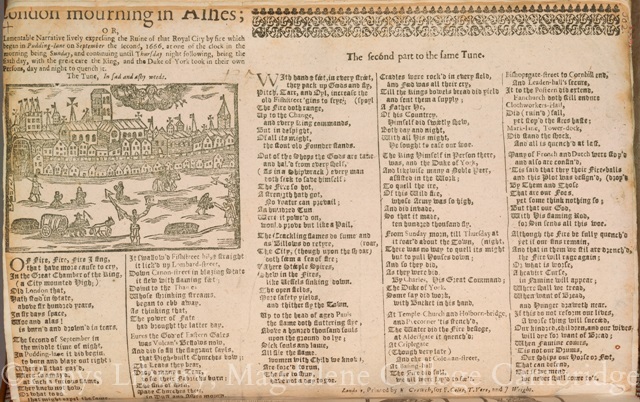

Item 5: Broadside Ballad: London Mourning in Ashes

Broadside ballads were very popular during the seventeenth century. Printed on cheap sheets of paper and sold in the street by chapmen or hawkers, ballads such as London Mourning in Ashes told stories that were not only read privately, but sung aloud and set to music. While they were often bawdy and promiscuous in nature, ballads might also take the form of a lament - as this example, which describes the 1666 Great Fire of London, demonstrates.

Pepys’s collection of broadside ballads, from which this image is taken, consists of more than 1,800 pieces, arranged thematically in five volumes under headings which include history, tragedy, humour, marriage, love, current affairs and morality.

Digitised facsimiles of the Pepys collection, together with further information concerning the history of broadside ballads more generally, can be viewed online via the English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA).

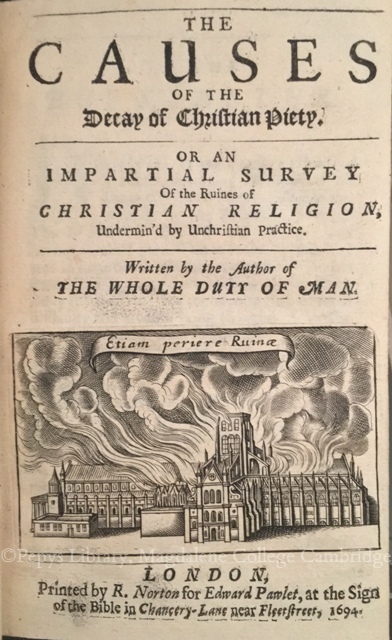

Item 6: Book: The causes of the decay of Christian piety, by Richard Allestree

First published anonymously in 1667, The causes of the decay of Christian piety is thought to have been written by the Oxford theologian, Richard Allestree (1619-1681). Pepys first records his interest in acquiring a copy of the work in a diary entry for January 1668, after it was recommended to him by the Bishop of Chester, George Hall (c.1613-1668).

Interestingly, while the title-page for the original 1667 edition includes a depiction of a blazing ship, the 1694 edition, shown here, displays instead an image of the old St. Paul’s Cathedral burning in the Great Fire of 1666.

It was believed by some at the time that the fire was a sign of God’s wrath, inflicted against the people of London for their sins and the use of this particular image here appears to reinforce this idea.

We hope you have enjoyed exploring these items online. To visit the Pepys Library in person, please see our opening times for members of the public.

Pepys Library Contact

For appointments to visit, photographic services and general enquiries, please contact the Special Collections Librarian.

Special Collections Librarian

Mrs Catherine Sutherland

pepyslibrary@magd.cam.ac.uk

01223 332115