Alumni

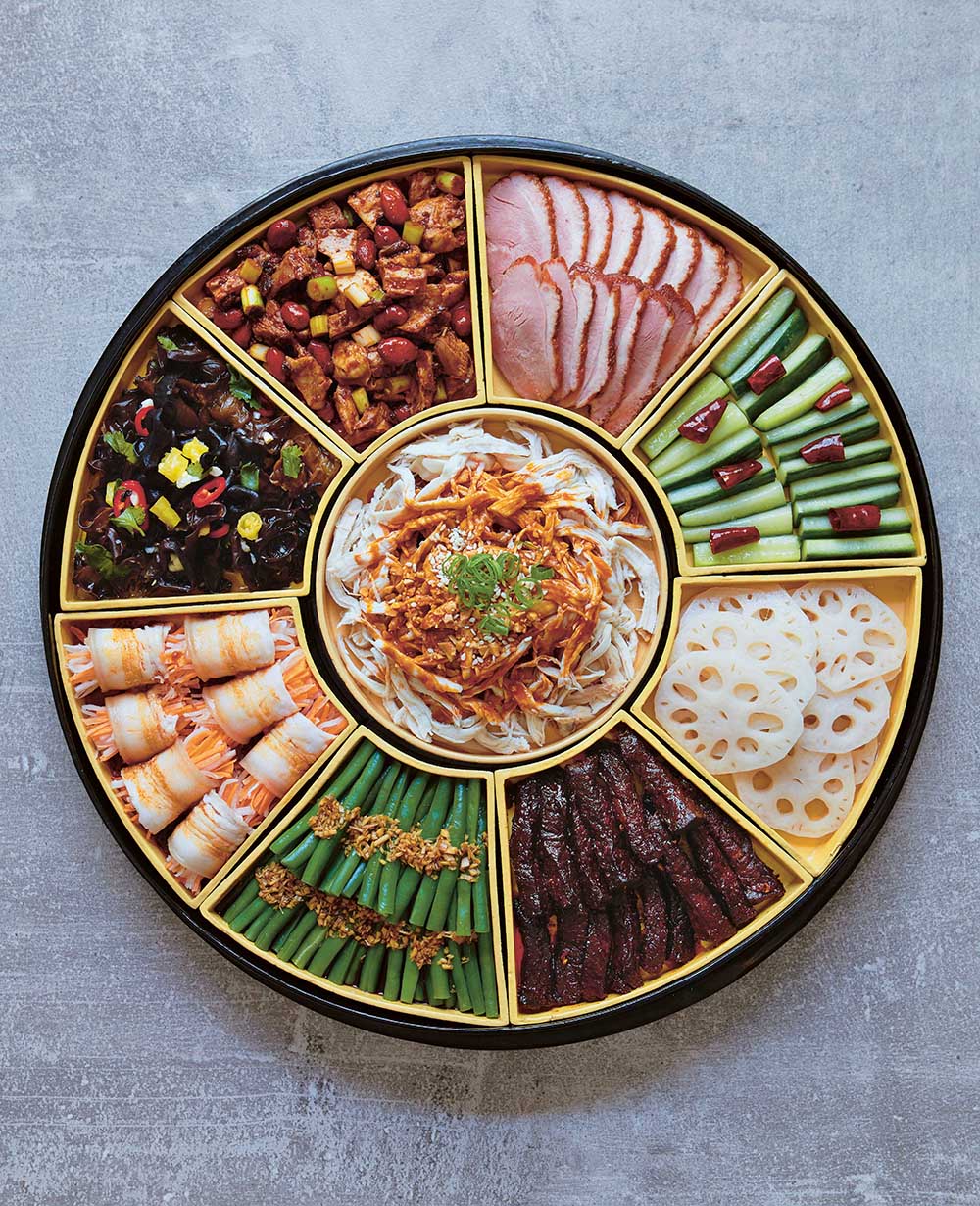

The Food of Sichuan

An interview with author and cook Ms Fuchsia Dunlop (1988).

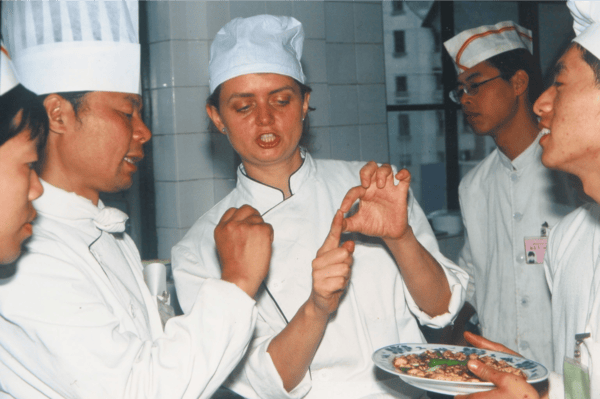

Fuchsia Dunlop is a cook and food-writer specialising in Chinese cuisine. She was the first Westerner to train at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine, and has spent much of the last two decades travelling around China, collecting recipes and exploring its food.

Almost twenty years after the publication of her first book Sichuan Cookery, declared by Observer Food Monthly as one of the ten greatest cookbooks of all time, Fuchsia revisits the region where her own culinary journey began, adding more than 50 new recipes to the original repertoire and accompanying them with her incomparable knowledge of the tastes, textures and sensations of Sichuanese cookery. We caught up with Fuchsia to ask her a few questions.

Q. What first led you to explore the world of Chinese food?

I'd always loved cooking and one of my early ambitions was to be a chef. While I wasn't sure what I wanted to do after leaving Magdalene, I imagined I'd end up in something related to food, and perhaps also travel. I first became interested in China through a sub-editing job at the BBC Monitoring Unit, not long after leaving Cambridge, and visited the country for the first time in 1992, backpacking. After that, I started Mandarin evening classes at Westminster University and eventually won a British Council Scholarship to attend Sichuan University in Chengdu. I was supposed to be studying Chinese minorities history but quickly became distracted by the amazing local food. I started asking restaurateurs if I could learn in their kitchens, and ended up becoming the first foreigner to train as a chef at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine. It was great fun and totally crazy in retrospect: I was one of three women in a class of about fifty young men (almost a repeat of Magdalene!), and all our classes were taught in Sichuan dialect.

Vintage shot of Fuchsia at cooking school in China. Image credit Lai Wu.

Q. You read English Literature here at Magdalene (as part of the first generation of Magdalene women, no less!) before becoming an acclaimed writer; how was your understanding of the art of writing shaped by your studies? Was there a writer in particular who inspired you, whether from your studies or otherwise?

My contemporaries used to joke that English was a completely useless subject - and I've actually been surprised by how incredibly useful it turned out to be! Firstly, it's just an immense privilege to have the time to read one's way through so many great classics of literature, and reading good writing is essential for anyone who wants to write. Also, reading critically teaches you some of the tools of the trade and makes you think deeply about how language works. By the time I left Magdalene I was instinctively a sharp editor, which turned out to be extremely useful in my career. And apart from the direct benefits of studying literature for an aspiring writer, learning how to pull the strings of language is invaluable for self-expression, persuasion and communication in any walk of life.

I didn't read any food writers as part of my course, but the highlight of my studies was undoubtedly Shakespeare: a joy. I was particularly lucky to have as a supervisor Tom Morris, who is now artistic director of the Bristol Old Vic but was then writing a PhD on Renaissance drama, who unlocked the subject for me. Foodwise, my writing idols include MFK Fisher, Fergus Henderson (for his recipes), John Lanchester (for The Debt to Pleasure), Claudia Roden (for her culinary ethnography) and the Qing Dynasty Chinese gastronomer Yuan Mei.

Q. From Barshu and Jianbing shops to Xi’an Impression and Master Wei, Brits are learning about the huge breadth of regional specialities across China, beyond the relatively narrow range of Cantonese classics they’re used to like sweet and sour pork or prawn toast. What do you think is likely to take off next in England?

There is no shortage of delicious Chinese regional foods for westerners to ‘discover’; the main problem is that immigration rules are now so tight that it's virtually impossible for new chefs to come over from China to work in the UK. So although I'm sure people here would love the cuisines of Yunnan and Guizhou, just for a couple of examples, I'm not sure who is going to bring them to public attention!

Q. You often describe Chinese food as treating vegetables as the star of the show, in particular with tofu as an ingredient in its own right rather than a mere meat substitute. As we become increasingly conscious about the environmental and ethical impact of consuming meat, what place do you think Chinese food has in this conversation?

The traditional Chinese diet can be a source of inspiration for anyone seeking to eat less meat, because the vegetable dishes are so delicious. Many are made either with small amounts of meat, or with fermented beany seasonings and pickles that bring rich umami flavours to the main vegetable ingredients - which means that you can eat less meat without feeling any loss of satisfaction. In a Chinese culinary context, a little meat can go a long way. Unfortunately westerners tend to think that typical Chinese restaurant food, which often emphasises meat, fish and poultry involves a lot of deep-frying and is heavily seasoned, is representative of the cuisine as a whole. Actually, the Chinese know far more about healthy and balanced eating than most westerners do; the ideas that food is medicine, and that a good diet is the absolute foundation of good health, are deeply engrained in Chinese culture.

Q. Who, dead or alive, would be your ideal dinner party guest and why?

The aforementioned Yuan Mei, an eighteenth-century Chinese gourmet and author of the seminal cookbook Recipes from the Garden of Contentment. He was a brilliant and eccentric scholar, a poet, a witty and irreverent writer and, of course, an extremely discerning eater. I'm sure he'd be great company.

If you would like to find out more or try any of Fuchsia’s mouth-watering recipes, The Food of Sichuan is available in all good bookstores and online sellers. Happy cooking!

This article was first published in Magdalene Matters Issue 50.