Library and Archives

‘A Disastrous Expedition’: I.A. Richards Caught Climbing the Roofs of Magdalene College

Thanks to the recent cataloguing of I.A. Richards’ notebooks, now available on our AtoM catalogue, Magdalene College has written evidence of its role in the history of night climbing in Cambridge.

The Night Climbers of Cambridge, published in 1937 by Noel Howard Symington under the pseudonym Whipplesnaith, was more than a guide to scaling the town’s rooftops; it was a phenomenon.1

Including such daring feats as the ‘Senate House leap’, a 6-foot jump between Caius College and its namesake, Symington’s account of night climbing is said to have kindled the first generation of urban explorers, the lineage of which persists today. The book was immensely popular in its time and was esteemed through several re-editions, being a more extensive instalment on the topic than other publications of its kind, such as The Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity, published anonymously in 1901 by Geoffrey Winthrop Young,2 and The Roof-Climber’s Guide to St John’s, published in 1921 by ‘A. Climber’.3

That Symington wrote these works at all is somewhat of a miracle, as the ramifications of being caught for night climbing could be life altering. In one article from the BBC, two students remember being ‘sent down’ in the 1960s, remarking how ‘One moment we were protected, isolated students, the next we had been abandoned, jobless, penniless...’.4 Although night climbing in Cambridge has long been an open secret, Symington suggests that policemen and dons were unlikely to accost a night climber, and younger dons were often climbing themselves, nevertheless, ‘outlaws keep no histories’, and there are precious few resources for the would-be historian of night climbing.5

It is this context that makes I.A. Richards’ notebook entitled Magdalene College Roofs and Climbs so valuable.6 Indeed, Sir Thomas James Roxburgh, Richards’ climbing partner, jokingly wonders in a letter containing photos of the climbs ‘if they are worth some cash, either directly or as a form of blackmail.’7 I.A. Richards was an eminent Professor at Magdalene and seminal figure in the development of English Literature as a degree, while Roxburgh was an accomplished civil servant. Perhaps such incriminating images in their lifetime would have been paid for quite handsomely!

Written during 1915, Richards’ last year as an undergraduate, the notebook is a rare account of night climbing from before Symington’s catalysing book. Richards’ accounts are thorough, recording his routes with a jeu d’esprit that resembles Young and Symington’s style. Each climb is written in the third person, referring to ‘the party’, ‘the leader’, and ‘the second man’.8 The first two climbs are initialled I.A.R. and T.J.Y.R., Richards and Roxburgh, and although the subsequent climbs are not initialled in the same way, it is likely that the two regularly climbed as a pair. In Roxburgh’s obituary, Richards remarks, ‘I think I introduced him to night-climbing.’ He goes on amiably:

‘He nearly always knew unusually well what he was doing, though I recall a moment on his first climb as leader of a rope on Tryfan when he had difficulty. We advised him to rest a minute or two and then try again. ‘Right you are!’ He remained a bit spread-eagled for a minute or two. Then, ‘I say, am I resting?’ To which we, looking up at the cliff, could only reply, ‘You know best, James.’9

Each recorded climb is accompanied by a small account of the weather and conditions for climbing: for example, ‘Sky overcast, weather cold, conditions slightly moist’.10 However, the conditions on the 28th of January 1915 illustrate a sign of the times: ‘Lights out everywhere in expectation of a Zeppelin raid. Special cares were desirable to avoid conspicuity.’11 On this ominous night in wartime, Richards juxtaposes the gloomy atmosphere with his own enthusiasm:

‘A variant which has the window at the right is easier but less delightful. The true climber will prefer to keep as much in the corner as is possible.’12

This satisfaction in challenge exemplifies the majority of Richards’ recorded climbs in which his passion is unmistakeable. However, no small part of this satisfaction is born from the risk of being caught, and the threat of discovery suffuses each one of the climbs: on January 23rd, it was ‘Hard to remain completely in shadows.’; on January 28th, ‘The tiles upon the kitchen roofs are in a burglar alarm condition.’ Finally, on February 1st, climbing the ‘Home Chimney Stack’, Richards’ luck ran out.

‘A disastrous expedition. Through the presence of a Jonah of another College, the party suffered a catastrophy [sic] of the second order, namely discovery, bringing with it the permanent loss of all climbing overhanging the street.’14

It was around 11pm on a ‘very clear and bright night’, with ‘light fresh rain’ and ‘a riding moon’, by all accounts a perfect night for climbing. But things quickly deteriorated.

‘The leader reached the foot of the final cleft and was considering further movements when a harsh and recognised voice shattered the beauty of the moony night. “What are yer doing hup there? What business have you hup there? You come down or you’ll be getting into trouble. If yer don’t come down I’ll fetch Mr Ramsey to yer.”’15

Sensing their defeat, the party scrambled to the ground with such anxiety than an ornamental bat broke off the wall and ‘fell with great emphasis upon the pavement below.’16 Unfortunately, Richards does not record what happens next, except to express his disappointment at no longer being able to climb on the slope overhanging the street. As for any repercussions of being caught, there is nothing recorded in the archives to indicate that he was punished, and indeed, as little as three weeks later, Richards was climbing again.

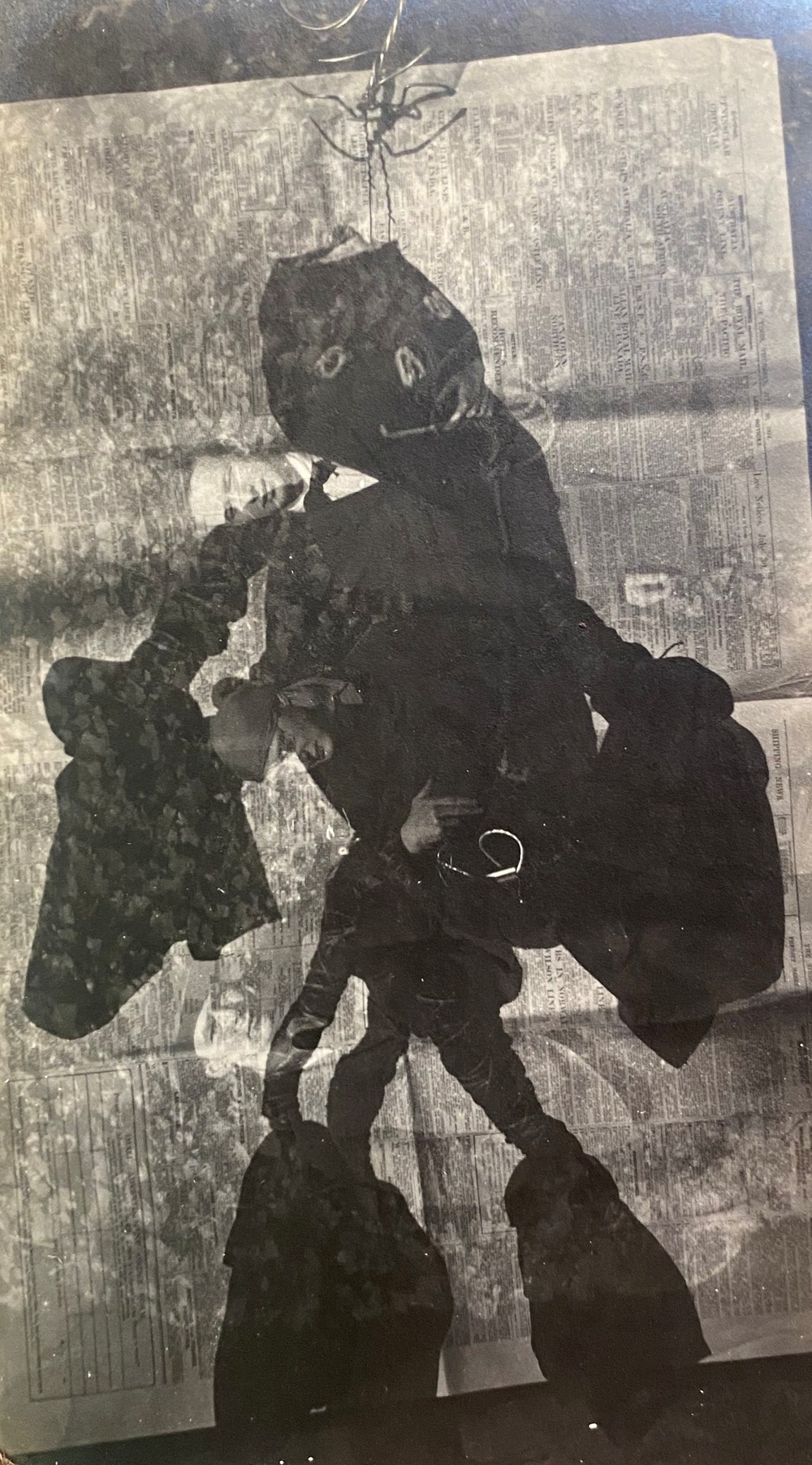

The final climb recorded in Richards’ Magdalene College Roofs and Climbs entitled ‘Clock Tower’ took place on March 2nd and was easily his most ambitious. Its objective was to hang an ‘imp’ or ‘devilkin’, a seemingly homemade doll or ‘poppet’, from the pinnacle of the clock tower. Richards and Roxburgh were then among the very first names added to the now long, illustrious tradition of depositing items at the summit of one’s climb in Cambridge, which reached its own pinnacle, amongst a litany of Santa hats on spires, when a full car was raised onto the roof of Senate House by students in 1958.

In 1915, however, the addition of the imp complicated the already severe climb by introducing the need for a 10-foot pole ‘unearthed from a gyp room in the Warren’ which would have to be hoisted up to the last foothold in order to raise the imp as high as the weathervane.17 After a failed first attempt that produced much tense clattering from the iron pole, the imp was secured. The success of their endeavour has been immortalised not only in photography but in poetry, too, written by Richards and published in the College magazine.

‘Imp of the moon! Imp of the moon!

Oh thing that no man reaches soon!’18

Richard and Roxburgh’s imp serves as an apt metaphor of the average climber, exceptional in his sense of mischief, devilry and daring. In The Night Climbers of Cambridge, many of the photographs are captioned with this sentiment in mind, what Symington calls ‘a love for the night and the thrill of darkness’,19 such as one student attempting the Senate House Leap, whose picture is accompanied by ‘Some airy devil hovers in the sky’ from King John, Act 3, Scene 2.20

Although it was known to some that I.A. Richards was an avid night climber as an undergraduate, this notebook provides written evidence of Magdalene being scaled during the sport’s heyday in the first half of the 20th century, despite its absence from the works of Symington, Young, and ‘Climber’, and from such a notable source! It is perhaps no wonder that Richards, who was such an avid mountaineer, would have delighted in scaling his College, no doubt in some cases for the first time. However, it must be remarked that it is only by his prior expertise in mountaineering that he was able to come away from his adventures unscathed, and even he was unable to avoid being caught. To the would-be night climber reading this, remember that your porter might not be so forgiving!

By Connor Johnston

Library Graduate Trainee 2024-25

All images used in this blog are the copyright of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College Cambridge. To reproduce these images in any format, including online, permission from the College must be sought. For further information please see the information on the page Old Library Photography and Filming.

References

1. Whipplesnaith. The night climbers of Cambridge. Cambridge: Oleander Press, reprinted in 2007.

2. Young, G.W. The roof-climber’s guide to Trinity: containing a practical description of all routes / Cambridge: W.P. Spalding, c.1901.

3. “A. Climber” [Anonymous]. The roof-climber’s guide to St John’s: with a plan and illustrations / Cambridge: Metcalfe, 1921.

4. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-47537261

5. Whipplesnaith. The night climbers of Cambridge. Cambridge: Oleander Press, reprinted in 2007. p.2

6. Richards, I.A. Climbing Diary. 1908-1917. Magdalene College Cambridge, Old Library, I.A. Richards Collection MCPP/IAR/I/1.

7. Roxburgh, T.J.Y. Letter to I.A. Richards, 1st January 1964. Magdalene College Cambridge, Old Library, I.A. Richards Collection Box 55.

8. Richards, I.A. Climbing Diary. 1908-1917. Magdalene College Cambridge, Old Library, I.A. Richards Collection MCPP/IAR/I/1. pp.5-9

9. Magdalene College Magazine. New Series 17, 1972-73, p.6

10. Richards, I.A. Climbing Diary. 1908-1917. Magdalene College Cambridge, Old Library, I.A. Richards Collection MCPP/IAR/I/1. p.5

11. Ibid

12. Ibid

13. Ibid, p.7

14. Ibid, p.9

15. Ibid

16. Ibid

17. Ibid

18. Magdalene College Magazine Vol. III, No. 5, No. 18, March 1915, p.349.

19. Whipplesnaith. The night climbers of Cambridge. Cambridge: Oleander Press, reprinted 2007.

20. Ibid